Graham Global Reception

✨ Countries Where Graham Thrived

In the UNITED STATES, where the technique was born, Graham’s legacy remains deeply rooted through institutions like the Martha Graham School, university programs (such as Juilliard, Ailey/Fordham BFA…) and touring activities of the Martha Graham Dance Company.

CANADA’s proximity to the U.S. helped Graham Technique take root in its dance landscape, especially in cities like Montreal and Vancouver. Institutions such as the École de danse contemporaine de Montréal and Simon Fraser University have long incorporated Graham training alongside other modern techniques. The influence extends to key companies like Toronto Dance Theatre and Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers, founded by Graham-trained artists, ensuring her legacy remains an integral part of Canadian contemporary dance education and performance.

Martha Graham’s influence reached the UNITED KINGDOM through her company tours in the 1950s, introducing British audiences and dancers to her innovative technique. Robert Cohan, a former Graham principal dancer, was key in founding the London Contemporary Dance School and London Contemporary Dance Theatre in 1966, where he adapted and transmitted Graham Technique within a British context. Other important Graham figures from New York—Jane Dudley, William Louther, and Noemi Lapzeson—were part of the company and became influential teachers in spreading the technique. Today, institutions like Middlesex University continue to teach Graham-based methods, notably the Cohan Method, while companies such as Rambert and Phoenix Dance Theatre carry on her artistic legacy.

Renowned teacher Jane Dudley teaching Graham at The Place. Photo: Anthony Crickmay.

Martha Graham’s company toured MEXICO starting in 1933, with follow-up visits in the 1960s and 1980s that firmly established her technique in the country’s dance culture. From Anna Sokolow’s early pedagogical influence to key figures like Guillermina Bravo, founder of the National Ballet of Mexico, Graham Technique became embedded in institutional dance training by the 1950s. Today, it continues to be taught at important centers such as CENADAC in Querétaro and INBA-affiliated schools, with its principles deeply influencing university programs, national companies, and generations of teachers who transmit Graham as both a historical foundation and a vibrant, living practice.

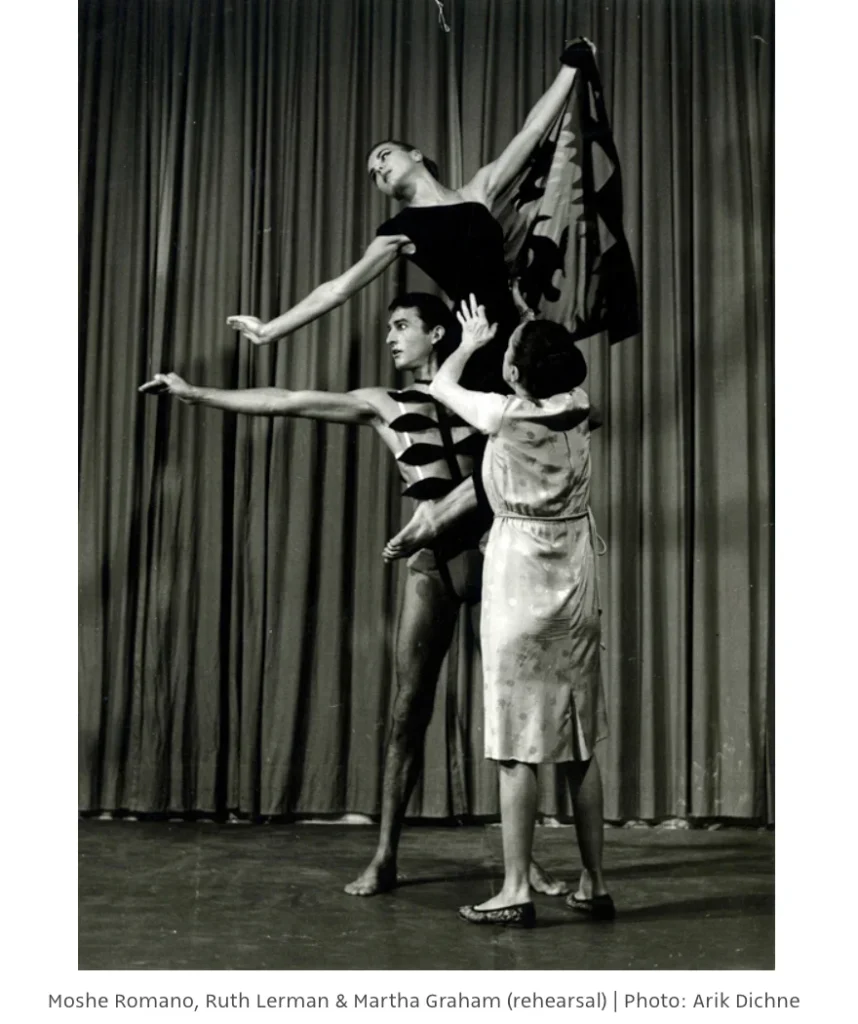

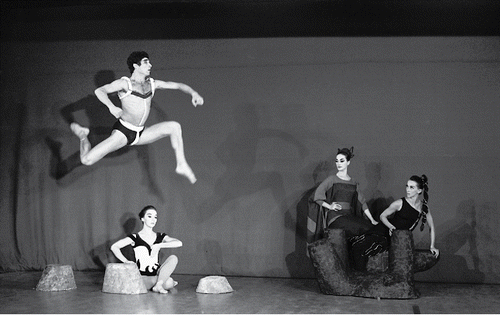

ISRAEL offers a particularly influential case. Graham Technique took root through early tours and the foundational role Martha Graham played in the creation of the Batsheva Dance Company in 1964, where she served as Artistic Advisor. Her protégée, American choreographer Anna Sokolow, also taught extensively in Israel, mentoring a generation of dancers and choreographers. The technique was deeply embedded in national training structures through institutions like Batsheva and the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance. Although the company eventually shifted toward Gaga and contemporary aesthetics, Graham’s imprint remains fundamental to the country’s dance heritage.

Batsheva dancers rehearsing with Martha Graham and performing Cave of the Heart.

CUBA has a dynamic contemporary dance scene where Graham Technique was introduced through international exchanges and Cuban dancers trained abroad, particularly during the mid-20th century. Cuban modern dance pioneers, such as Ramiro Guerra and Alicia Alonso, incorporated elements of Graham’s expressive style and technique into their work, blending it with Afro-Cuban and Caribbean dance traditions. Institutions like the National School of Ballet and the Cuban National Dance Company (Danza Contemporánea de Cuba) have included Graham-based training in their curricula, fostering a distinctive hybrid modern dance style. Today, Graham’s legacy remains influential in Cuba’s contemporary dance education and performance, contributing to the island’s unique fusion of Western modernism and Afro-Caribbean cultural heritage.

In SENEGAL, Graham Technique found a meaningful foothold through Mudra Afrique, a pioneering school founded in Dakar in 1977 by Maurice Béjart with support from the Senegalese government. Under the leadership of Germaine Acogny—often called the “mother of contemporary African dance”—the school incorporated Graham-based practices alongside African dance traditions and European modern techniques. Acogny, who trained in part with Graham-influenced teachers, played a key role in integrating these methods into the curriculum. Although Mudra Afrique closed in the 1980s, its legacy endures through ongoing artistic exchanges, educational residencies, and the transmission of hybrid techniques that include Graham elements within a broader, decolonized approach to modern dance in Senegal and beyond.

SOUTH AFRICA has integrated Graham Technique within its contemporary dance education, especially after the end of apartheid when cultural exchange expanded. Institutions like the University of Cape Town’s School of Dance and the Moving Into Dance company have incorporated Graham-based methods alongside traditional African dance forms, creating a distinctive fusion that reflects South Africa’s complex cultural identity. Key figures such as Dada Masilo and Gregory Maqoma have drawn from both Graham’s modern dance principles and indigenous movement vocabularies to develop innovative choreographies that resonate locally and internationally. This blending exemplifies a postcolonial approach to modern dance, where Graham’s legacy is adapted within a decolonized framework to reflect South African realities.

ARGENTINA and BRAZIL have vibrant contemporary dance scenes where Graham Technique has been integrated through the work of dancers trained in the United States and Europe. In Argentina, Buenos Aires serves as a hub for modern dance, with institutions such as the National University of Arts (UNA) incorporating Graham-based training alongside other contemporary techniques. Influential choreographers and teachers who studied Graham abroad have helped embed the technique within Argentina’s contemporary dance education and repertory. Similarly, Brazil’s major cities—São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro—have embraced Graham’s legacy within their national modern dance development, blending it with Afro-Brazilian and indigenous movement traditions. Universities like the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and dance companies such as Grupo Corpo reflect this fusion, where Graham Technique informs both pedagogy and choreography, contributing to a rich, hybrid modern dance culture.

In JAPAN and SOUTH KOREA, American-trained dancers brought Graham Technique back during the mid-20th century, incorporating it into university programs such as Tokyo University of the Arts and Korea National University of Arts. Key figures and choreographers helped weave Graham’s principles into national modern dance education and performance, supporting the development of vibrant contemporary dance scenes that blend Western modern dance with local traditions.

AUSTRALIA developed a strong modern dance tradition significantly influenced by Graham Technique, introduced primarily through mid-20th century tours and American-trained dancers who settled there. Institutions such as the Australian Ballet School and the Victorian College of the Arts incorporated Graham-based training alongside other modern techniques, helping to shape a distinctive modern dance vocabulary. Companies like Australian Dance Theatre and Chunky Move, while rooted in modern dance traditions, have evolved to engage with Indigenous and contemporary cultural expressions, reflecting Australia’s diverse artistic landscape.

🙄 European Countries with Limited Reception of Graham Technique

In France, Graham Technique struggled to gain traction due to the dominance of ballet and Ausdruckstanz, notably the influence of figures like Françoise Dupuy and Karin Waehner. The technique was often dismissed as overly rigid or culturally foreign.

In Germany, the strong heritage of Ausdruckstanz and pioneers such as Mary Wigman shaped post-war dance education. Institutions favored local traditions and later gravitated toward Tanztheater and conceptual approaches, leaving little space for American modernism.

In Italy, national conservatories emphasized classical ballet, and contemporary dance only entered the curriculum in the late 1980s. Graham remained marginal, often taught only in private studios or workshops.

Spain’s isolation under Francoist rule (1939–1975) curtailed exposure to international trends, including modern dance. Graham only gained visibility through returning expatriates and international collaborations after the democratic transition.

In Belgium, the explosive rise of postmodern and conceptual dance in the 1980s and 1990s—epitomized by P.A.R.T.S. and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker—shifted attention away from codified techniques like Graham in favor of composition and improvisation-based methods.

Conclusion

The global reach of Graham Technique reflects the unique political, institutional, and cultural contexts of each country. While North America, Mexico, and certain regions in Asia and Africa embraced Graham as a foundational pillar of modern dance, parts of Europe favored their own historical traditions or gravitated toward abstract and conceptual contemporary aesthetics. This divergence highlights the rich diversity of global dance ecosystems and underscores how local contexts shape the transmission and adaptation of artistic legacies.